The Taylor Group of Companies thrive by the mantra of service

Founded in 1927, the Taylor Group of Companies (Taylor) has evolved from a struggling small family business into a privately-owned global industrial powerhouse.

Poised to celebrate 100 years of business in 2027, third-generation Taylors lead the company, with the fourth generation coming up in the ranks. Taylor has 16 companies under its umbrella, and 1,807 employees worldwide.

Even though Taylor is extremely successful today, with awards spilling over bookshelves and accolades pouring in from every direction, dark clouds loomed many times over the progression of the company.

In the Beginning

Long before the company began, the Taylor clan immigrated from Northern Ireland, around the time of the American Revolution, and settled in Scuffeltown, SC. The Alexander Taylors moved to Choctaw County, settling near French Camp, before the start of the Civil War.

As a young boy, Alec Taylor, born in 1901, “loved to tinker with cars,” recalled Wilson Taylor, Alec’s brother. When their dad died abruptly at age 50, Alec, the oldest child, ran the farm and the gristmill until he moved to Tallahatchie County and then back to French Camp as a shade tree mechanic.

Alec suffered maladies as a young man: he had a ruptured appendix and almost died; he suffered from malaria; and he almost perished from scarlet fever.

In 1922, Alec and his wife, Ruby Leon Turner Taylor, and their baby daughter, Edith, moved 24 miles east to Louisville, an important railroad town, living in a boarding house. “We moved everything we had in a Model T, and it wasn’t anywhere near loaded,” he recalled to his son, William Alexander “Bill” Taylor, Jr. During one of Alec’s illnesses, Edith stood too close to a furnace and her clothes caught fire. Badly burned, she spent months convalescing.

Alec took a mechanic’s job with the repair department of Rhodes Motor Company, a shop he acquired with J.M. Hight in 1927, naming it Taylor’s Garage and Machine Shop. The genesis of the company was housed in a converted livery stable, with a dirt floor covered in motor oil. Concrete was scarce.

In 1928, the Taylors were doing well enough to build a house on 620 North Columbus Avenue. However, in October 1929, the stock market collapsed. To keep the struggling company afloat, Ruby fed boarders and made handkerchiefs she sold to Goldsmith’s in Memphis. Though financially stressed, Alec was able to buy out Hight’s interest in time for lenders to threaten to close the business. In fact, they asked Winston County Sheriff Ellis to put a lock on the door; he refused. Alec regrouped. For a while, Alec traded work for school and government coupons, which he used to pay employees. “Sometimes in business, it pays to be a little ignorant,” recalled Bill, with a laugh.

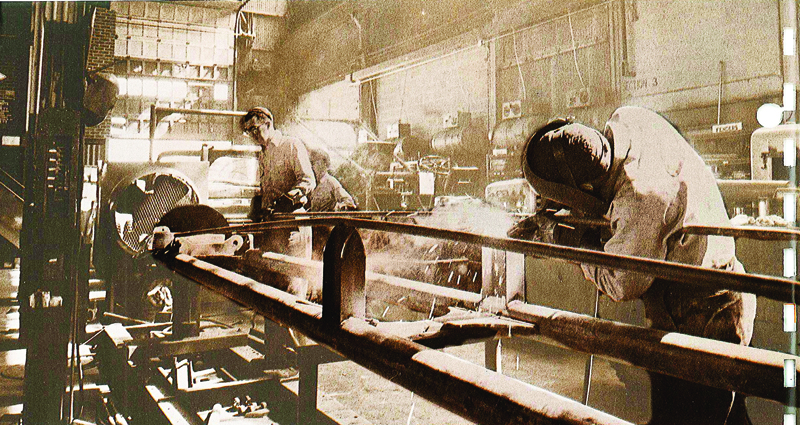

Bill was born around the time Alec expanded the business to a woodworking shop, gristmill, and feed mill. He bought the D.L. Fair Lumber Company machine shop in 1935 and recognized the need for log trailers and skidders for handling timber. So, he learned to build them.

On May 31, 1946, the company became Taylor Machine Works (TMW), starting with a total of 54 Loggers Dreams on order. Soon, Alec led the nation in sales for industrial stationary power units. By 1947, Taylor had 168 employees. “One of my dad’s wisest traits was to surround himself with men of great abilities,” observed Bill.

Then the bottom fell out. Employment dropped to 102; net earnings showed a $1,226 loss for fiscal 1949-50.

Alec, seeking “the green light” for guidance from God, decided to invest in the Pasture Dream, a new agricultural product he designed, which pushed TMW into the black again.

Simply Filling Needs

TMW’s foray into the forklift and material-handling field began in 1952, with the Yardster, designed for small sawmills that could not afford a conventional forklift. The following year, noting that the pulpwood industry needed an inexpensive way to load wood from a truck directly onto a railcar, Alec produced the Pulpwood Dream.

Trouble brewed again in fiscal 1953-54, when unpredictable weather patterns left TMW with 1,306 unsold Pasture Dreams, representing an inventory of nearly $300,000. Assets declined, as did working capital, net worth, and shipments. As soon as TMW recovered, another fiscal crisis hit in 1956: a widespread drought depressed the sales of the Pasture Dream. The need for working capital became critical.

“Once again, Dad went to his knees in prayer,” recalled Bill.

Then Alec spotted an ad for the First National Bank of Chicago, promoting working capital for new businesses. Bankers provided a $275,000 loan in short-term financing, with a 5% interest rate, and a five-year loan of $100,000 at 5-1/2% interest. Once again solvent, Alec bought land across Highway 15 from the plant and opened the popular restaurant, Aunt Nannie’s Kitchen.

In 1964, TMW set a record surpassing the $10 million mark, with annual sales of $412 million. The next year, Paul Harvey’s noon broadcast began with “first to a tiny town, the name of which was Louisville, population less than 6,000! And yet every storefront is a shiny showcase, and every lawn is a garden, and the handsome neo-classic courthouse was both antebellum and new—all that I’d always hoped, that somehow the South could preserve the best of the past, while making the most of the future—was there …”

A 1966 comprehensive market analysis showed Alec that TMW couldn’t afford to have so many diversified directions and needed a better-structured management organization. Alec regrouped again. Hoping to provide employees with a balanced lifestyle, Alec built the Spiritual Center in the middle of the TMW factory complex, home to the “Taylor Choir.” Ironically, it was finished around the time Alec died suddenly, at the age of 66.

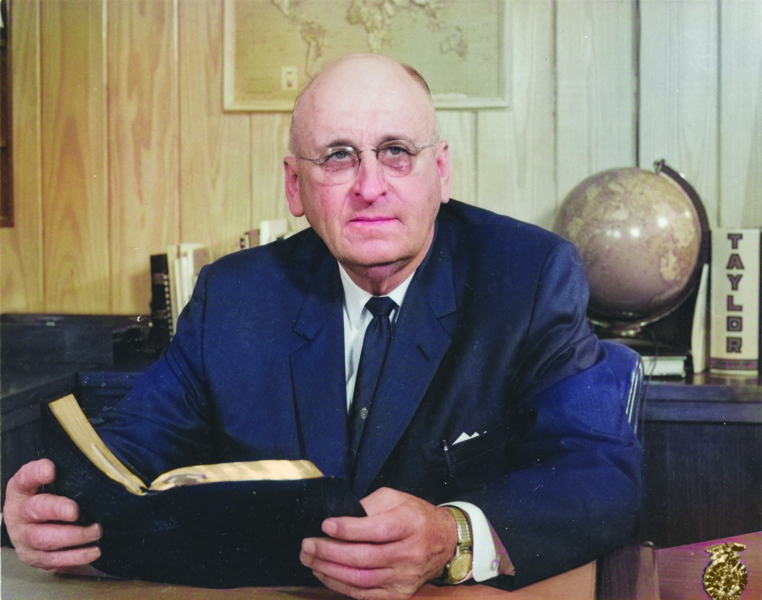

Alec’s wake was held in the Spiritual Center. In the lobby of TMW corporate offices, a life-sized portrait of Alec, sitting at his desk with an open Bible in his hands, commemorates his life’s work. He was a long-standing member of First Baptist Church of Louisville, a regular in his Monday morning prayer group, involved with the Rotary Club and French Camp Academy, former president of the National Manufacturers Association, and more.

Before his death, “Papa Taylor always went swimming with us before we got ready to go to church,” Bill’s daughter, Teresa Lynne Taylor Ktsanes, recalled.

The Second Generation

Bill showed up at TMW the following Monday, ready to run the company.

“I knew 500 employees would be looking at me and speculating about whether I could fill Dad’s shoes,” he recalled. The employees didn’t realize that for 14 years, Bill had worked in lockstep with his dad.

“My father had set these words down on paper: Faith. Vision. Work.” said Bill. “They were a succinct summary of his personal and business philosophy. It became the motto for our company. Those words are in big letters above the main gate of our Louisville manufacturing complex. Faith is how we take the first step, Vision is how we see the future, and Work is how we overcome the obstacles. These words still state our core values, and we see no reason to tinker with them.”

However, Bill believed there was a need for a new symbol to represent the company’s image, to exemplify the Taylor spirit. “Big Red” was the result: “You can depend on Big Red.”

One of Bill’s first orders of business: pay taxes.

“The only way for us to raise enough tax money was to sell the Taylor Research Farm and timberlands acquired,” lamented Bill.

In the 1970s, TMW sailed into rough waters with unions trying to organize employees. Seniority became a cause of discontent, as younger workers were better trained.

“Our employees organizing a union was one of the bitterest pills I’ve had to swallow,” admitted Bill. On Feb. 5, 1971, TMW inked a three-year contract with the United Steelworkers of America, Local #7772. When contract negotiations broke down in 1974, union employees went on strike for six months, a time he recalled was “unhappy, painful.”

However, good things were happening at TMW. In 1972, the company delivered its 10,000th Big Red machine to Georgia-Pacific Corporation.

In 1975, the unveiling of the first 120,000-pound lift truck, which could lift and drive with 60 tons, marked TMW’s arrival as the builder of the biggest, strongest forklift on earth.

In 1977, Bill’s son, W. A. “Lex” Taylor III, was finishing a business degree at Mississippi State University while working daily at TMW. Planning the company’s 50th anniversary for June 3 was the first significant assignment for Teresa, then a high school senior. Bill’s second son, Robert Davis Taylor, was an elementary school student.

“My first job,” recalled Lex, “was sweeping out the receiving bay, keeping the dock clean. Dad paid me out of his back pocket.” Lex was 15.

Bill described Lex as “rational, dependable, serious-minded, and perceptive, a rock-solid man at a young age. Sturdy and deep rooted as an oak.”

More Storm Clouds

Even though 1979 was a profitable year, economic storm clouds gathered, making the first half of the 1980s “a nightmare,” recalled Bill. “Except for God’s grace, I don’t believe we would’ve survived. We had to make tough decisions. We had to lay off almost 400 workers; some had been with us for 30 years. All salaried employees, including us, had salaries sharply reduced. We stopped contributions to our pension plan. We liquidated assets and inventories. Things still looked bleak.”

TMW closed plants in West Memphis and Bay Springs, a tough assignment for young Lex. Salaries were reduced again.

“We were about tapped out and faced with two options: sell the company and put everything we personally owned on the line and try holding out a little longer to save TMW. The second choice would, of course, mean corporate and personal bankruptcy if we couldn’t pull it off. Selling out was tempting.” Total employment fell to 312.

Bill turned to intense Bible study and then came up with an answer: “ my wife Mitzi and I put it all on the line. We personally endorsed the TMW notes, and we moved ahead on faith.”

Bill soon learned about a new type of financing, based on receivables and asset financing, with Barclays Bank of London. “They gave us a new breath of life,” he said.

The Third Generation

In a secret board meeting in 1986, Lex, then 31, was elected the third president of TMW. Bill remained board chair. (Lex is now board chair and CEO of the Taylor Group of Companies. Robert is president and COO.)

Meanwhile, Robert’s first recollection of working at TMW was “stuffing envelopes—and I absolutely hated it,” he recalled, with a laugh.

“Robert,” Bill described, “has a quick mind, strong leadership skills, and a first-rate personality.”

Teresa established herself as one of the nation’s sharpest manufacturing promoters. Of her many-faceted hat, she directs W.A. Taylor Galleries, based on a passion of Bill’s, and manages advertising, public relations, and market research operations for Taylor.

In 1989, TMW delivered its 20,000th machine to the Universal Maritime Service Corporation in Port Newark, NJ.

The 1990s to the Aughts

A couple of highs and lows hit the 1990s: product liability, “a very negative impact to the bottom line,” and a new state incentive program, said Bill.

“Litigation for companies on product liability was at an all-time high, even for manufacturers who had done everything reasonable to make products safe,” said Bill, who hired a staff attorney to manage those issues and other legal matters.

On the flip side, Gov. Kirk Fordice and Jimmy Heidel, his economic development director, strongly believed in state funding for the expansion of existing in-state industries.

“They made available a new form of industrial revenue bonds at interest rates far lower than we could get at any bank,” said Bill.

Business was good during most of the 1990s, which gave TMW a huge growth window, said Lex.

“It was clearly the time to ramp up the company, to take us to a whole new level so far as capacity was concerned,” he said.

In 1992, the Taylor family established a holding company, The Taylor Group, Inc. (Taylor).

TMW became a prime manufacturer for the intermodal industry, which “certainly set us on the way to growth that was unheard of … this new design brought us to the forefront,” Bill added.

Jerry Shiverdecker, co-author with Bill on The Taylor Story, published in 2002, said Bill “has a self-deprecating ‘aw shucks’ demeanor that masks his intelligence.”

Before Bill died in 2007, he said “we continue to tell our people that we’ll always engineer and build what the customers need. It’s a slogan that defined our business model decades ago and continues to be our compass, guiding our philosophy daily.”

In 2002, Taylor delivered its 30,000th machine (Big Red) to Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad at its Los Angeles Intermodal Facility.

In 2008, Taylor opened the Quail Ridge Lodge & Conference Center, a vision of Bill’s to allow customers, dealers, and vendors to meet in a relaxed atmosphere. Located about 12 miles from corporate headquarters, Quail Ridge has skeet, trap shooting, hunting, and fishing on a lake stocked with bass, crappie, bream, and catfish. A common evening includes grilled lamb chops, a warm slice of pecan pie with vanilla ice cream, evening brandy, and cigars around a stone fireplace. Guests retreat to lakeside cottages, or a game room for sports watching.

“Food and fellowship bring people together,” said Bill.

The Teens

In 2012, Taylor introduced Vision Plus, the next-generation pedestrian detection aid, as an available upgrade on X-Series trucks.

Two years later, Winston County, centered on Lexington, suffered severe damage from EF3 and EF4 tornados. Taylor rallied behind its family of employees.

In 2015, Taylor produced its 40,000th machine, an XH-180, to Constellium in West Virginia.

During President Trump’s “Made in America” celebration on July 17, 2017, as part of his “Putting America First” campaign, Taylor was the chosen Mississippi company to attend, presenting one of their forklifts.

In 2017, Taylor Defense Products was formed to provide material handling and logistics products to the U.S. military and its allies. Taylor Logistics was founded in 2018 to oversee and manage various components of production.

In 2019, Taylor produced the world’s first zero emissions, battery-electric container handler. “Electrification of mobile material handling equipment is an exciting and challenging effort, but is also developing very quickly,” said Matt Hillyer, director of engineering.

Also, that year, Taylor released the Taylor DREAM Cab as a standard option on the X-Series truck, boasting the industry’s largest cabin area. Also, Taylor International LLC was formed.

The 2020s

When COVID-19 hit, like many companies, Taylor was adversely affected.

“Business is off over 35 percent year on year, and we’re 50 to 65 percent off from what we’d planned to do, based on our budgets,” reported Lex.

An upside: Taylor became an authorized Terberg distributor to seven southeastern states. The relationship between the fourth- and fifth generation Terberg company and the third- and fourth generation Taylor resulted in the construction of a manufacturing and distribution plant for making terminal tractors in Columbus.

Joe Max Higgins, CEO of the Golden Triangle Development LINK, said “anytime you can get an international company that’s a worldwide leader in their industrial sector forming a joint venture with an iconic U.S. company like Taylor ‘Big Red,’ you have a winner!”

In 2021, Taylor established Taylor Construction Equipment. In September, Taylor became a Hyundai dealer of construction equipment in Tennessee. Taylor’s Tool & Supply opened in the footprint of the original Taylor’s Garage.

In 2023, Taylor presented SSA Marine with the company’s 50,000th machine at SSA Oakland, California. That same year, Mississippi senators praised the Taylors for winning a $96 million U.S. Army contract for Taylor Defense to support the Rough Terrain Container Handler Modernization program. Sen. Roger Wicker called Taylor Defense “a world-class company that makes some of the best heavy-duty equipment for our U.S. military.” Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith called the sizeable contract “a true vote of confidence in the terrific work done … in support of our armed forces.”

Also, Taylor’s Sudden Service opened a new facility in Philadelphia as a primary hub for rebuilds and remans, which “mimics our large R&D building in Louisville,” said Joe Cowart, Taylor’s director of industrial engineering and quality.

Taylor remains heavily involved in local matters, especially healthcare. When the Winston County Community Hospital faced imminent closure or being sold, Lex was appointed the first president of the Winston County Medical Foundation, a non-profit organization formed to take over the hospital. In 2023, Taylor opened a new employee private health clinic, Vigilant Health Clinic, available at no cost to employees and their families in Louisville and Philadelphia who participate in Taylor’s medical health plan.

A Celebratory Year

So far, 2024 has been a banner year for Taylor. The company opened Taylor’s Tool & Supply, with Ace Hardware, in Starkville, and Taylor Tire & Lube Center in Louisville.

In February, Taylor acquired 85 percent of controlling shares of CVS Ferrari, an Italian forklift company with plants in Piacenza and Parma.

“CVS has found a new home with an industrial investor that can provide long-term stability and adequate resources to enhance the company’s development further,” said Federico Zanotti, CEO of CVS Ferrari.

The Terberg Taylor Americas manufacturing plant opened in February, mirroring the exact proven production process of the Benschop Netherlands.

On August 1, Taylor Machine Works delivered the first five battery-electric, zero-emission top handlers to Yusen Terminals in the Port of Los Angeles. The handlers can stack 100,000-pound containers up to six units high.

“It’s a major first step in our journey to zero emissions,” said Alan McCorkle, president and CEO of Yusen Terminal.

The Fourth Generation

Now, Taylor is moving forward with a fourth generation.

Lex’s children are Alexis Grace Taylor, Bailey Taylor, a schoolteacher, and Alex Taylor, a management trainee for the company.

Teresa has one child, Matthew Ktsanes, a management trainee for the company; four stepchildren: Kristin Lundquist, Jimmy Ktsanes, Zach Ktsanes, and Marc Ktsanes; and 10 grandchildren.

Robert has three sons: Robert Davis Taylor, Jr., director of Sudden Service; Zachary “Zach” Calvin Taylor, director of Taylor Power; and William Grayson Taylor, a sales representative for Taylor Construction Equipment. Davis has three young children, representing the fifth generation of Taylors: R.D. Taylor, Cal Taylor, and Emma Taylor.

“We’ll continue to build on faith, vision, and work, and doing the right thing next consistently,” vowed Davis Taylor.

“Our future certainly looks bright as we drive forward and move into the environmental front with electric and hydrogen powered products, support to refurbish and/or build logistical equipment for the defense of our country, partner with a family-owned company in the Netherlands to build terminal tractors here in America, and continue to manufacture the finest heavy-lift equipment and standby and prime power generators in the world,” said Lex.

“With God’s grace, our story continues.”